[ad_1]

Researchers from the Jamia Millia Islamia used satellite data to keep track of land surface temperatures (LST) and the evolution of the NCR city’s land use patterns from May to June between 2010 and 2019.

Urban areas in Gurgaon increased 60% from 2010 to 2019, with most of this derived from farmlands that saw an almost equal decline (61%) in area over this period, their calculations found.

“The main reason behind the rising land surface temperature in Gurgaon seems to be the steep rise in urban built-up spaces built over the open permeable land areas,” said lead author Manisha Dabral Malcoti who carried out the study with professors Hina Zia and Chitrarekha Kabre.

The peer-reviewed paper – ‘Impact of Urbanization on Land Use Land Cover Change and Land Surface Temperature in a Satellite Town’ – was published in the ‘Advancements in Urban Environmental Studies’ book published by Springer earlier this February.

The research underscores the impact of urban heat island effect, when a city experiences warmer temperatures than nearby rural/greener areas as concrete and building structures absorb and retain heat from the atmosphere.

Malcoti, a research scholar at the university’s department of architecture and ekistics, said temperatures will keep rising if policymakers and authorities don’t keep urban heat island effect in mind.

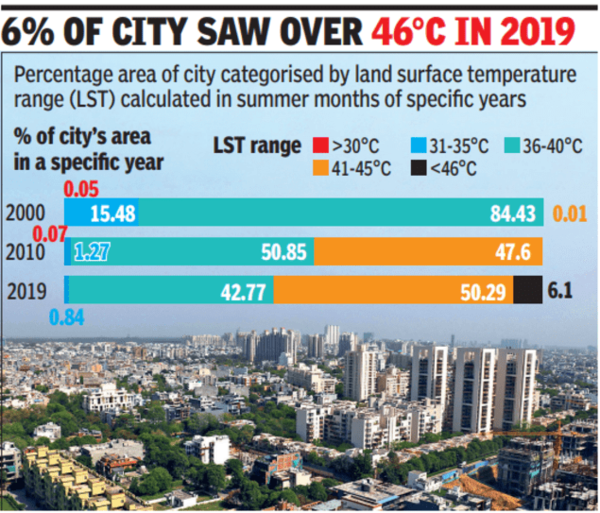

“The speed with which heat waves are becoming a silent disaster calls for the implementation of immediate short and long-term mitigation strategies. These heat waves are normally exacerbated by the urban heat island effect. Authorities should start with the identification of heat hotspots in a city using satellite data and IMD data, and invest in the latest technologies to develop a framework for tracking and modelling heat hotspot data. This way, support and resources can be prioritised,” she said. For instance, land surface temperatures mapped by the researchers found that in the year 2000, a vast majority – 84% – of Gurgaon’s total area was in the range of 36-40 degrees Celsius during summers. This came down to around 50% by 2010, when around 47% of the city’s surface logged temperatures between 41-45 degrees Celsius.

In 2019, around 6% of Gurgaon’s land surface recorded temperatures over 46 degrees Celsius, and over half of the city was in the 41°C to 45°C range.

These figures also match the monthly average maximum temperatures obtained from the India Meteorological Department (IMD). In 2000, the maximum monthly average ambient temperature in May and June was 36.3°C, and this increased to 37.5°C in 2019.

On long-term measures, the study’s lead author said authorities need to start approving development plans that take into consideration climatic considerations such as minimum greenery mandated within a specific area and the use of construction materials that can reflect sunlight instead of absorbing it.

“Most importantly, building codes should be redefined to undertake heatwave risk mitigation and align all new construction work with it. Urban heat island (UHI) mitigation elements are currently absent from the majority of bylaws and urban planning policies. India is also struggling with climate change as the instances of heatwaves are becoming frequent and intense. With the fast rate of urbanization of rural areas and the resultant high UHI intensity, the vulnerable population of cities will be at a serious health risk.” Experts who weren’t involved in the study also said cities need to start building climate resilient buildings.

“Water bodies and open green spaces act as carbon sinks, which help reduce temperatures. In our cities, we find that gradually, the open spaces are reducing in the greed for development. The recent IPCC report has shown that if cities want to create a sustainable environment, then they need to create more water bodies and encourage greenery in cities,” said Anjal Prakash, who is one of the lead authors of the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

[ad_2]

Source link